Plague Redux: Santa Rosalia’s Protean Iconography

di Tina Waldeier Bizzarro Iconocrazia 17/2020 - "Iconocratic Studies. In memory of Sarah Jordan Lippert" (Vol. 1), SaggiWorks of art always spring from those who have faced the danger, gone to the very end of an experience, to the point beyond which no human being can go. The further one dares to go, the more decent, the more personal, the more unique a life becomes.[1]

During the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic, we have recalled Santa Rosalia and her purgative campaign against la peste bubbonica, which afflicted Palermo and environs after arriving in Sicily on a ship from Tunis in 1624. The ship, captained by the already plague-afflicted Muhammad Calavà and brought into Palermo in 1624 by Sicily’s Viceroy Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia, unleashed its already-infected crew and its rats on the city, spreading the plague throughout the island of Sicily and beyond. Santa Rosalia’s cleansing panacea for Palermo emanated from her dead body, her moribund bones, which had lain buried and dormant in her wet and numinous mountain retreat for almost five—maybe sixteen—centuries, depending on which version of her hagiography you select. Palermo was delivered from the Black Death between 9 June and 15 July of 1625 in a type of processional “passover” after Rosalia’s relics were processed through the city streets, at her behest in one of her earthly appearances.

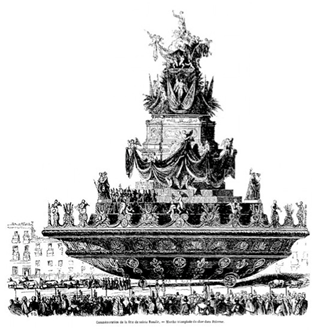

Through the power of her cadaverous and salvific bones, “La Santuzza,” or the little Saint, halted the bubonic plague that had beset the city and emerged as Palermo’s uncontested heroine and guardian through today. “Viva Palermu e Santa Rusalia,” is the chant, in Sicilian dialect, passionately wailed as she is paraded in effigy through the streets on her festa or feast day in mid-July. In an ironic twist of fate, the Coronavirus pandemic thwarted the 2020 celebration of Palermo’s 396th annual U Fistinu (Sicilian for la festa) in her honor. Two eponymous celebrations were halted: the magnificent multi-day July celebration, complete with a colossal boat-shaped chariot (or carro trionfale), garlands of roses, angels, serenading musicians, and the cult statue of Santa Rosalia—all drawn through the city streets by a team of oxen; the second, the early September evening torch-lit pilgrimage climb up the strada vecchia to visit and venerate Rosalia in her cave sanctuary on Palermo’s Monte Pellegrino, where her relics were found in 1624.

Who would not hope for such an instant deliverance from disease? Indeed, Rosalia has entered once again into the forefront of Christian prayer during the Coronavirus pandemic. She is being invoked by the people of Palermo to halt the Coronavirus of 2020. She is trending on social media, Twitter, and Instagram. On the Facebook page of EWTN, the Catholic television channel in the United States, one can find a prayer to Santa Rosalia—complete with a video slowly gliding across the famous van Dyck image of her triumphal and ecstatic epiphany of 1624—that through her intercession, deliverance from the Coronavirus and all other harm be effected (Fig. 1).[2]We have all been faced with a long, hard look at life and death throughout this pandemic, and many have returned to prayer through the intercession of saints like the hermit Rosalia, whose life of renunciation, contemplation, and prayer offers up an example of penitence and hope.

Fig. 1. Anthony van Dyck, Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-Stricken of Palermo, 1624. Oil on canvas, 39¼ x 29. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/creativecommons.org.

The story of the Lady Patroness Rosalia of Palermo is protean; her birthplace and time fungible.[3] And, like the amoebic narrative that has been spun from her life, she is always associated with water, the sea, marine life, and the freshwater drippings from the limestone cave where she lived out most of her short life, devoted to prayer and mortification. The story of Rosalia and water has not yet been told. Rather, most narratives featuring Rosalia testify to her difficult and painful life in the two stone caves where she lived, leaving off the thread of her iconographical, spiritual, and spatial attachment to water. Weaving this aqueous thread into Rosalia’s short life of spiritual withdrawal to her spongy and wet limestone cave, we have a richer palimpsest of her mythic presence within the Sicilian faith system and the still-annual devotion accorded her on her two feast days.[4]

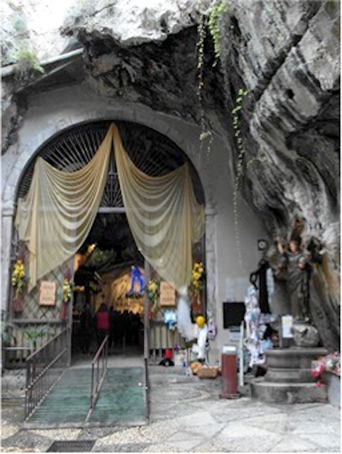

Atop Monte Pellegrino, looming large over the western side of the bay of Palermo, isolated from all other mountains along the fertile conca d’oro, Rosalia’s moist grotto-cave looks down almost 2000 feet onto the Sicilian capital and the Tyrrhenian Sea.[5]Since the first quarter of the seventeenth century, a Baroque church façade crowns this peak, masking the more numinous and primitive porous-stoned cave sanctuary opening, plunging more than eighty feet deep into the mountain. The steep serpentine road up to the sanctuary from Palermo below, the strada vecchia,is the site of the traditional and intense acchianata, the penitential pilgrimage on the 3rd of September, the evening before the anniversary of her death (Fig. 2).[6] Men and women walk barefooted—some ardent pilgrims dropping to their knees—in a procession illuminated with torches, from below the hill and up the grand stairwell, praying to St. Rosalia for favors or to thank her for graces received. Mounting the eighty or so steps that lead to the sanctuary façade crowning the high promontory, framing the dimly lit cave, they are greeted with fresher air, the sounds of water dripping from the cave walls and into the Holy Well in the atrium, and a statue of the Christian naiad, Rosalia (Fig. 3).[7] The feast commemorating the translation of her relics from mountain-top to city-center slowly and dramatically unfolds for about a week before the feast on the 15th of July.

Fig. 2. Baroque façade of Santa Rosalia’s Cave Sanctuary, 1624. Palermo. View from near top of stairwell toward the sanctuary façade. Photo credit: author.

Fig. 3. Open-air atrium of St. Rosalia’s Sanctuary, behind the exterior stone portal. Palermo. Photo credit: author.

Santa Rosalia’s history—like that of many an early Christian saint—is murky, unstable, and patchworked.[8] She does not attract much popular attention at all before the end of the sixteenth century, although there are iconographical traces of her story long before that. Two distinct tales and chronologies have evolved. One nineteenth-century writer, most certainly reflecting a longstanding legend with contemporary pictorial witness, located Rosalia as a first-century beneficent Middle Eastern hostess, alongside the apostles of Jesus Christ in Jerusalem. Just after Christ’s crucifixion and death, Rosalia converts to his creed—on Pentecost, the Christian feast commemorating the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Christ’s apostles that bestowed the gift of tongues on them so they might go afar and spread his good word.[9]

This predominantly orally transmitted narrative is, I believe, most fundamental to the story of Rosalia and the one that most adequately encompasses all subsequent iconography that has developed around the “Little Saint.” George Glieg, a visitor to Sicily in the years around 1837, records that Santa Rosalia was indeed this Middle Eastern woman, as the story was told to him by a local priest with whom he was lodging:

According to the padre, Santa Rosalia was a lady of rank and fortune; if I recollect right, a princess, who dwelt near Jerusalem during the days of the Apostles, and was converted by them on the day of Pentecost. She lived in great splendor, and exercised much hospitality towards the believers, till the persecution consequent on the martyrdom of Stephen arose; when she was compelled to flee, attended by a single maid, and to seek an asylum in a country whither the authority of the high priest could not extend. As Providence would have it, the ship in which she embarked was bound for Sicily, and carried her safely to Palermo, in the vicinity of which she lived a life of seclusion during many years. Santa Rosalia was no nun, neither was her attendant; but they kept up very little intercourse with the world, dividing their time, both by day and night, between the practice of devotion and the exercise of charity. Santa Rosalia died at last, without having attracted any great share of public attention, and was buried; but her merits had not been wasted. There occurred, some years afterwards, a grievous sickness in Sicily, which cut down the population by hundreds, and which all the efforts of the physicians proved inadequate to arrest. The whole island, indeed was in mourning; when, one day, a devout monk, walking out of Palermo into the country, was met, near the cell which Santa Rosalia used to inhabit, by a being manifestly not of earthly mould. There was a glory round the head of the stranger, whose robes were white and shining; while from her eyes a lustre beamed so pure and piercing, that the monk could scarce venture to look upon it. “I am Santa Rosalia,” said the vision, in a voice whose tones were music. “I hold a high place in the family of the Blessed Virgin. She has sent me to say that, provided you will raise my bones, and carry them in solemn procession through Palermo, the plague will cease.” The monk, bowing low, returned in all haste to the city, and communicated the substance of what had befallen. The bones of the saint were exhumed; priests and magistrates bore them through the streets with lighted candles and bands of music; and that very day there came a change of wind, which wafted the infection from the shores. I may add that, in honour of the good saint, a convent was forthwith built over the spot from which her body was taken; and that the precious relics, being there deposited, are still shewn to the pious and the liberal, greatly to the edification, as well as to the financial benefit, of the society.[10]

Glieg’s recounting of the oral yarn, which was most likely current long before and long after 1837, confirms a tradition of popular belief in the early Christian solidity and august reputation of this female saint. It provides evidence of Rosalia’s virginal life of chastity, charity, and painful seclusion, her first-hand epiphany of the Holy Spirit, her primary and authentic witness to the life of Christ, her association with flight, voyage, and traversing the seas in a boat, her dogged determination to witness to Christ, and finally the miraculous and healing bones of her buried body.

Her association with the sea and translocation maintains a permanent element of her feast-day celebration in which a giant barge is erected and carried through the streets of Palermo to the harbor, where she was thought to arrive, no doubt (Figs. 4 and 5).[11] No other versions of Santa Rosalia’s iconography explain or account for this significant artifact or for her enduring association with water—the waters of sea passage and the watery environment of her mountain cave.

Fig. 4. The carro trionfale or triumphal barge of Santa Rosalia in Palermo. Illustration by “P.B,” from the French periodical “l’Illustration” of 27 July 1850.

Fig. 5. The carro trionfale of Santa Rosalia from the 395th anniversary celebration of her festa in 2019. Photo credit: author.

In Glieg’s words again:

There are many festivals in Palermo in honour of departed worthies, but, in point of magnificence, that of Santa Rosalia far surpasses them all. It occurs on the anniversary of the miracle which her bones are said to have performed, and is kept with processions, and feastings, and fire-works, and all sorts of public shows, at which the king and his court, equally with the people, attend. For some weeks previous to the arrival of the great day, all Palermo is in commotion. Frameworks of timber are fabricated, which the carpenters arrange along the Marino (stet), whence the fire-works may be shewn (stet); and an enormous car is made, which, being covered over with silken hangings, supports upon poles a lofty stage, and is surmounted by an image of the saint, half hidden in a mass of silken clouds. The car itself is supported upon low truck-wheels; but on its sides there are four other wheels of a wider span, which never touch the ground, but are turned round and round by a winch, which some of the persons whom the hangings conceal set in motion. At an early on the morning of St. Rosalia’s day—as soon, indeed, as it is light—the car is discovered on the Marino. On the stage, and surrounding the images of the saint, are groups of women, dressed in showy robes, and covered with flowers; while, tied to the four large wheels, are little children, whom the silks and feathery wings, fastened to their shoulders cause to represent angels. Then there is a sounding of trumpets, and ringing of bells, which, together with a volley of patteraros (stet), warn the surrounding country that the saint has appeared among men. No sooner is this clamour heard, than, from far and near, country-people are seen driving their bullocks towards the city, which they yoke in a long string to the car. The farmer, indeed, who should refuse to lend his cattle for this purpose, could not hope to prosper at the coming vintage; and happy is he who, arriving first at the Marino, succeeds in placing his bullock next the car. Then is the machine set in motion; while, from the windows and balconies hats and handkerchiefs wave, and the air is rent with the tumult of voices, the braying of trumpets, and the roar of artillery. Thus slowly, and with frequent halts, the saint is conveyed through the main street towards the further gateway; while, as it moves, the large wheels are turned slowly round, and the poor little angels go up and down, till they are as effectually delivered from the weight of their morning’s meal as if they were at sea in a gale of wind.[12]

Indeed, Rosalia’s translocation over water in a boat from the Holy Land and her spongy stone cave location make sense via this more fundamental narrative. This boat transport will as well link Rosalia to other early Christian saints—such as Saint Mary Magdalene, Saint-Devote, Saint Mary Jacobé, and Saint Mary Salomé—forming a structural hagiographical connection in terms the way in which their sanctity is guaranteed via their perilous odyssey through the turbulent waters of the Mediterranean.

The alternative yarn that is spun increases in popularity from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries onward; it is more tinctured with fairy-tale deeds, events, and language—much more appealing, no doubt, to the political arenas of the Angevin and later Aragonese and Bourbon occupation of Sicily.[13] This francophilic version ranks one Rosalia Sinibaldo (c. 1130–1166), a Norman princess, descendant of none other than the French king and later Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne (748–814), living among the Norman nobility (some say harem!) of King Ruggero II of Sicily, in Palermo’s Arabo-Byzantine Palazzo dei Normanni. Her father was Duke Sinibaldo, Lord of Quisquinia and Monte delle Rose (probably from whence her name evolved), located between Bivona and Frizzi in the Palermo area, and her mother was Mary Guiscard, cousin of the Norman king Ruggero II. As damsel to King Ruggero’s wife, Queen Sibilla, she undergoes many a picaresque episode—and even the “royal” version of Rosalia’s story has narratives that turn corners and diverge from this one—such as being saved from the attack of a wild animal by one Count Baldovino, the future king of Jerusalem. (Some accounts have Baldovino saving King Ruggero from the wild beast.) As a reward for his chivalric bravery, and we see here how the tale begins to become more paternalistic and medievalizing, King Ruggero II awards Baldovino the young beautiful Rosalia in marriage. But he is not as lucky as he had hoped for, because the princess spurns him.

Rosalia flatly rejected the offer, deciding instead to renounce earthly pleasures and satisfy her innate eremitical yearnings to retreat from society. She took to the Basilian monastery of Saint Salvatore in Palermo, some sources say, and there is evidence of many a Greek Catholic monastery/convent in Sicily during the early Middle Ages, when Sicily formed part of the Byzantine Empire.[14] When she could no longer abide the visits and hectoring of her parents and Baldovino, she escaped to a cave close to a Benedictine monastery, in the far reaches of her paternal estate in Quisquina, about twenty miles from Sicily’s Madonie mountains, in the province of Agrigento. This is the first of the mountain caves with which she is ultimately associated. Eventually she relocated to her signature mountaintop cave above Palermo on Monte Pellegrino (Mountain of the Pilgrim), in a cell built over a still-extant well, where she lived out her final twelve or so years as a hermit (Figs. 6 and 7).[15] This Norman Rosalia lived out a more agonized and excruciating life of meditating on Scripture, fasting and keeping vigil, sleeping on a rock, and imitating the life of Christ crucified; the crucifix became a steady symbol in Rosalia’s iconography.[16] Rosalia then receded into history’s darker corners. We hear very little of her for more than 300 years, although her memory lived on below the surface of religious consciousness.[17]

Fig. 6. View into Santa Rosalia’s Cave Chapel, from W.F. Ainsworth’s All ’round the World: An Illustrated Record of Voyages, Travels and Adventures in All Parts of the Globe, with Two Hundred Illustrations, 1866–1870.

. Ainsworth’s All ’round the World: An Illustrated

Fig. 7. View into Santa Rosalia’s Cave Chapel today, looking in from atrium of 1866. Photo credit: author.

When the plague struck Palermo in early May 1624, Rosalia’s memory and body were exhumed. The Baroque seventeenth century formed new threads and visual metaphors of Rosalia’s supple and mutable legend. The ever-transgressive Rosalia, one version of her life tells us, reappeared first to a forty-seven-year-old sick woman, Girolama La Gattuta, who, after climbing Monte Pellegrino and drinking some refreshing water dripping from Rosalia’s cave walls, was cured. Girolama was told, in an angelic vision, to dig inside the cave, and two months later, the bones of a woman were found, cleaned, and brought to Palermo’s Archbishop Giannettino Doria. Seven months later, in February of 1625, Rosalia appeared again to a hunter, Vincenzo Bonello, who had just lost his wife. Rosalia instructed Bonello to process her relics through the city for delivery from the plague. After the translation and procession of her relics, Palermo was liberated from the plague.[18]At this point in her pictorial history, Santa Rosalia is clad in a coarse, usually brown, woolen robe, corded around her waist, with reddish-blond hair worn loose and topped by a crown of roses. Her attributes, while varying, usually include: a skull, a book, a crucifix, a martyr’s palm, a crown of roses, a lily of chastity, and a pilgrim’s staff for climbing or a pick-axe for chiseling away at the mountain walls.

One other slightly divergent thread of this over-determined and pastiched hagiography regarding the finding of Rosalia’s bones bears mentioning, in light of its resonance in a statue sculpted in Santa Rosalia’s honor, which still graces her cave sanctuary (Fig. 8).[19] During the 1625 outbreak of the Black Plague, one writer claims, a hermit had a vision in which the ever-subversive Saint Rosalia instructed him to search for her remains. The hermit led a group of monks who searched and found the cave on Mount Pellegrino where she had died, discovering, sheathed in rock crystal, the body of Saint Rosalia. Gregorio Tedesco’s magnificent Baroque sculpture of the sleeping saint in dreamy ecstasy, with lips parted and hand under cheek while the other grasps the cross to her breast, could not be more evocative—with its cold marble and gold sheathing—of an eternal crystalline rock chrysalis, the shell of the uncorrupted virgin hermit. She is indeed an exemplum of a Christ-like life, an analogue in sculpted stone, of the epitaphios or full-length embroidered image of the dead Christ, used to cover the bread and wine in the “Divine Liturgy” of the Byzantine church. She is, like Christ, an offering, a sacrificial lamb, lying in her grave beneath the altar of sacrifice, participating in the godhead.[20]

Fig. 8. Gregorio Tedesco, Santa Rosalia in Ecstasy, sculpture in marble and gold, 17th century. Santa Rosalia’s Cave Sanctuary, Monte Pellegrino, Palermo. Photo credit: author.

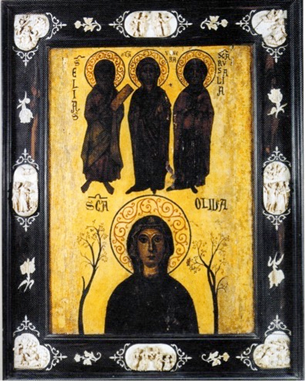

A short historiography of Santa Rosalia’s images helps to explain the many shifts and transformations in the stages of her pictorial legend.[21] In some of the earliest representations we have of Rosalia from the thirteenth century, she is cast in the Byzantine iconic tradition, standing fully frontally, as a traditional early Christian saint, perhaps a Basilian nun, accompanied by one male and three other female saints: Saint Elias, Saint Venera, and Saint Oliva(Fig. 9).[22] This icon could easily have had earlier Byzantine prototypes, as the pictorial tradition of the icon alters little over centuries. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Rosalia’s legend spread beyond Sicily through Italy into Tuscany with paintings of her by, for example, Francesco Traini (1321–1365) and Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448–1494), which present a more nubile Rosalia, in the bejeweled clothing of nobility and with a crown of roses replacing her more severe head veil (Fig. 10).[23] Rosalia is transformed into a monastic in the sixteenth century, dressed by some painters in either Benedictine or Franciscan robes, probably triggered by the Franciscan control and oversight of the Monte Pellegrino sanctuary at this time.[24]

Fig. 9. Icon of St. Oliva (at bottom) with Saints Elias, Venera, and Rosalia (at top, left to right), 13th century. Museo Diocesano di Palermo, Palermo. Photo credit: author.

Fig. 10. Francesco Traini (c. 1321–1365), Santa Rosalia (detail) from a five-part polyptych of Madonna and Child with Saints, 1330–1350. Museo Nazionale di San Mateo, Pisa. Photo credit: author.

By 1625, with the painting of Vincenzo La Barbera (“Santa Rosalia Intercedes for the City of Palermo,” Fig. 11),[25] we have arrived at most of the ingredients of the current iconography of La Santuzza—with a new poignant, theatrical twist. She is painted dressed in the brown monastic garb of the Franciscans, kneeling on Monte Pellegrino, above the conca d’oro and Palermo’s waterfront and beneath a heavenly golden epiphany within clouds borne by angels. The Trinity of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are seated within the buoyant clouds, flanking a sphere of the earth surmounted by a gold cross. Mary, Christ’s mother, humbly folds her arms across her chest, to Christ’s right and the viewer’s left. An orange-winged angel bears Rosalia’s crown of roses. Before her knees lay her symbols: the book or Bible, the skull of penitence and death, and the lily of purity.

Fig. 11. Vincenzo La Barbera (1577–1652), Santa Rosalia Intercedes for the City of Palermo, 1625. Museum Diocesano di Palermo, Palermo. Photo credit: author.

Noteworthy more for its Baroque theatrical conceits than for its inherent beauty, La Barbera’s painting presents Santa Rosalia as a seventeenth-century sufferer of the plague, tainted and pock-marked, interceding to God for her people, fully experiencing their pain. The inside of Santa Rosalia’s right hand as well as the outside of her left hand are blackened by the bubones or boils—of the extremely virulent bacterium, Y pestis—which gave the bubonic plague its name. In this Baroque and truly theatrical piece, the saint herself is seen as living and dying of the plague. As she intercedes for her fellow Palermitans in 1625, she has become one of them. This painting clearly shows the influence of images of St. Francis of Assisi (1181/2–1226) receiving the stigmata atop Mt. Alvernia in Tuscany. Rosalia, however, has not received the mark of the Lord’s passion; she is marred instead with the boils of the bubonic plague. Her darkened right hand has already begun to show the first signs of death: the pink-purplish spots of decomposition of the skin, resulting in the ugly and painful death from the plague, memorialized in the children’s rhymed dance: “Ring-a-ring-a-rosies, a pocket full of posies, ashes, ashes (or a tissue, a tissue; or A-tishoo! A-tishoo! —coughing sound of plague victims), we all fall down.”[26] In this painting, Rosalia has become her story; she has succumbed. She is the savior of the city, the island.

The year 1624 saw the enrichment, refinement, and establishment of the definitive modern pictorial iconography of the plague saint in the work of the Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck, who resided in Sicily for eighteen months (Fig. 1). In one of his best-known and one of his five surviving paintings of Santa Rosalia made during his days in quarantine, van Dyck limned a floating, ecstatic, limpid Rosalia, transformed and pulled upward by a celestial magnet, amidst a flurry of erotic, cavorting angels and drapery. She maintains the brown habit of the Franciscans and her namesake roses. This van Dyck painting was one of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s very first acquisitions, bought a year after the museum’s founding in 1870, and it was scheduled to be a highlight of the celebration of the “Making of the Met” Exhibition in honor of the museum’s 150th anniversary, ironically postponed, in a cruel twist of fate, by the Coronavirus outbreak of February 2020.[27]

In all versions of Rosalia’s story and iconography, however, some facts are constant: she was a young, noble, and virginal woman, escaping the demands of society (from either Jerusalem or her promised suitor in the Palazzo dei Normanni) to a mountain cave where she became a teenage hermit, renouncing all earthly pleasures. She was a transgressive force, staging appearances to various men and women, disturbing the status quo—not unlike the mother of Christ. While it is harder to understand the lives of female saints, outnumbered by about 8 to 1 by male saints in the Catholic Church’s “Roman Calendar,” Santa Rosalia’s story bridges a number of biographical structures established for women since the early Christian period—biographical structures dependent on family associations and not spiritual achievement.[28]Santa Rosalia was not the virginal youth, hidden from public view, living within the confines of a family until married off, like chattel, to a respectful, and usually older, suitor. She was not societally submissive or passive; rather, she courageously flew in the face of these norms, choosing instead a severe life of childless, self-enforced, penitential exile and devotion to Christ, alone in a watery cave. She became fossilized in her cave home, as she determined to see God alone—not a very feminine choice in the first or twelfth centuries!

Whether a contemporary of the principal early Christian female martyrs of Palermo she eclipsed—Santa Agata, Santa Ninfa, Santa Oliva, and Santa Cristina, an exceptional array of female honorifics—or a twelfth-century Norman princess, she becomes the main patroness of Palermo, and her feast day, celebrated with luxurious fanfare and pomp, is one of the most spectacular in all of the Mediterranean—even today.[29] Since the seventeenth century, Santa Rosalia is indeed summoned back from the grave in her biannual feste—the most fabulous of which is the celebration of the discovery of her bones in mid-July. Starting on about 10 July, this magnificent celebration of “La Santuzza” extends through her feast day on the 15th, complete with an enormous boat-shaped float, bedecked with effigies of angels floating amidst clouds of fabric, garlands of roses, serenading musicians, and the cult statue of Santa Rosalia (Fig. 5). All of this ritual paraphernalia is drawn through the streets by local teams of oxen, as described in Glieg’s account of almost 200 years earlier, from the city-center to the marina by the sea, from whence Rosalia first reached the island of Sicily!

This transformative ritual proposes, at a very real and visceral level, to resurrect Rosalia from the dead through the ritual apparatus of fireworks, which call her to life as her effigy leaves the sanctuary. “Viva Santa Rusalia!” the teaming crowds roar, as she “walks” through the streets of Palermo, probably retracing the path she took upon her arrival there countless centuries ago from across the sea—these footsteps somehow still echoing through her palimpsest life story. Time has folded in on this ritual procession, and Palermo’s streets and alleyways become transformed into the holy ground of the first century. This new reality mirrors where heaven and earth meet and where the forbidden and perfect spaces of Rosalia’s earthly domain touch our quotidian spaces of home, city, and piazza, turning our reality upside down. Marking this break with cyclical time are the ritual panoply of sermons, prayers, purifying candles and incense, chants, hymns, dances, processions, fireworks, and ritual foods—foods that come from, echo, and smell of Santa Rosalia’s sea. Everywhere, during the festa days, you smell the odor of the ritualized, specialized, meaningful foods prepared only for these feast days: wild fennel in pasta with sardines; the “sfincione,” a bread covered with onions, tomato sauce and caciocavallo, a stretched, cured cheese; anchovies cooked with oregano and breadcrumbs; octopus and mussels steamed in sea water, served with sliced lemons; and the festa’s signature dish, little snails or “babaluci,” steamed with garlic and parsley, consumed in the thousands.

The iconography of her sea passage, her cave retreat, and her virginal insistence on a life united only with Christ, link Santa Rosalia, I believe, to at least four other early Christian saints with similar stories, symbols, and ritual celebrations: Saint Mary Salomé, Saint Mary Jacobé, Saint Mary Magdalene—Middle Eastern and all eventually of France—and Saint-Devote of Corsica and Monaco. Their lives mirror those of the so-called “Desert Mothers” or ammas, Christian ascetics who chose the deserts of Egypt, Israel, and Syria in which to live lives of pain, suffering, and deprivation.

The story of Mary Magdalene is better known perhaps than those of the three other fleeing female saints. Her sea escape from the Holy Land in the first century to a port in France is part of the French Catholic salvation history. Her story links up Saints Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobé and locates in a small town in the Camargue region of France, near Arles in Provence, called Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, whose eponymous name reveals the protagonists of the story.

A frail boat without sails or oars arrived from the Holy Land at the shore of this small fishing town in c. 45 ad, carrying refugees from Herod Agrippa’s persecutions: Mary Salomé, mother of St. James Major; Mary Jacobé, sister (or cousin) to the Mother of Christ; Mary Magdalene; Lazarus, who preached in Marseille and became its first bishop; Martha, sister of Lazarus; Sidonius, the blind man from Jericho; and Maximinus, who later became the first bishop of Aix and, along with Mary Magdalene, began the evangelization of Aix-en-Provence that spread to all of France. A local gypsy, Sara, threw her garments out onto the water to act as a raft for the party; she was later converted to Christ by Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobé, who stayed with Sara in the small coastal town, not much bigger now than it was then. The others dispersed to evangelize Gaul.

Mary Magdalene, also known as Mary of Magdala, took the road to the mountain of Sainte-Baume, where she found herself a humid, inaccessible grotto, wherein she expiated for her sins of the flesh for thirty years. After Mary Magdalene’s death, a basilica was erected in Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, about nine miles away from her cave retreat, to house the relic of her head.[30] A statue of Mary Magdalene from this church bears a striking iconographical resemblance to Tedesco’s statue of Santa Rosalia in her cave hideaway—the recumbent posture, the long hair, the stone pillow, and the cross (compare Figs. 8 and 12). The Magdalene also shares Santa Rosalia’s tale of difficult and dangerous transport across the Mediterranean, of penitential suffering, and eternally vigilant sleep on her stone pillow.

Fig. 12. Statue of Saint Mary Magdalene, from Church of St. Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, near Aix-en-Provence, France. Photo credit: author.

Saints Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobé remained in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, preaching the word of Jesus, lending the town their names in 1838. Like Santa Rosalia, they were in Jerusalem with Christ. They saw Christ on the cross and witnessed his Resurrection. They die several months apart, and Saint-Trophîme from Arles buried them. The two holy women, along with the gypsy Sara who helped them, were buried near the small oratory they built. After several miracles occurred in their names, their bodies were excavated by King René, Count of Provence, in 1448, who found their stone pillow, embedded in the column of the crypt church, along with a spring of pure water that shot forth, nourishing the well of the church. The association of these three saints’ stories with Rosalia is cogent and begs ideological comparison.

Their feast day is celebrated on 25 May at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in a fashion similar to that of Santa Rosalia, including a three-day celebration and the lowering of the relics and their statues from the high chapel of the church out onto to the streets (Fig. 13). The statues of Saints Mary Salomé and Mary Jacobé, in their small boat, are ceremoniously hauled to the sea by zealous Confraternity members, where they and their boat are partially immersed into the white waves from whence they arrived. The gypsy Saint Sara, who attracts thousands of gypsies with their painted caravans to the small town, is given the same ritual reverence. The fervent gypsies ceremoniously carry and immerse the dark-faced effigy of Sara in her small boat into the waters of the Mediterranean, amidst much wailing, crying, and chanting of, “Vive Sainte-Sara.” Saint Sara is costumed in multiple and multicolored mantles, reminiscent of the raft-like cape she is reported to have tossed to the two Marys arriving in their small frail boat to her coast during the first century (Fig. 14).

Fig. 13. The confraternities immerse the statues of Sainte-Marie Jacobé and Sainte-Marie Salomé into the sea. Annual Procession and Celebration at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France, on 25–26 May 2019. Photo credit: author.

Fig. 14. Saint Sara being carried in the sea, at the Pèlerinage des Gitans (Pilgrimage of the Gypsies) at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France, 25–26 May 2019. Photo credit: author.

Photo credit: author.

The story of the less well-known Monegasque patroness Sainte-Dévote, an early fourth-century Corsican martyr who is ceremonially and liturgically venerated annually in Monaco on her feast day of 27 January, features similar iconographies, sea voyages, and rituals. After her martyrdom by Diocletian in 303 or 304, her body was stolen by some faithful Christians and placed in a boat that journeyed of its own will to Monaco. There she was retrieved from her vessel by Christian believers and buried in a chapel in the valley Gaumates, near the port.[31] The seventeenth-century Pope Honorius named her patroness of Monaco. On her feast day, an evening procession of the confraternities bearing her relics winds down to the sea, a dove is released into the air, and there is a ritual blessing of the sea and the fishermen. Then, in front of the church dedicated to St.-Dévote, the boat of her delivery to Monaco, made new each year, is set afire amidst fireworks.

All of these Christian processions create transformative countersites or heterotopias, in the language of Michel Foucault, which turn our realities upside down. The sites that are created in these ritual dramas are privileged, forbidden, and perfect—all at the same time—mapping graves, dark cave sanctuaries, sea waves, bone relics, holy springs of water, and bodies of dead saints. They mark liminal places where heaven and earth meet, where time collapses, where thresholds tempt us to taste the eternal. We break with traditional time and enter the locus of epiphany and transformation—like Santa Rosalia did.

Santa Rosalia broke the bonds of family and home, willfully escaping to a mountaintop den. Living as a subterranean anchorite in a leaky, watery cavity, within a wild and uncultivated landscape, self-exiled and marginalized, she manifested her undaunted love of Christ, her bridegroom. More likely a Middle Eastern desert mother than a Norman princess, she echoed the chthonic origins of her craggy hollow. Rosalia became endowed with the sacred power of the water that springs from its hilltop source there, the archetypal symbol of life, of purification. Even today, upon descending from the mountaintop sanctuary, one can continue to participate in the sweet bitterness of Rosalia’s life, with the digestive ideale of Amaro della Santuzza, available in the small surrounding kiosks, at the foot of the sanctuary! Indeed, in the Greco-Byzantine tradition of hagiasmata, or holy springs, Rosalia’s aqueous hollow was and still is incorporated into the very ecclesiastical foundation and probably accounts for its early and continuing reputation as a center of pilgrimage. Yes, Rosalia’s bones dispatched the plague of 1624, but the curative fluids of Rosalia’s mountaintop outpost had been active for centuries before and continued to inform her iconography, her hagiography, and the architecture of her shrine home.

Gaston Bachelard, in his Poetics of Space, attempted an anthropology of the imagination, particularly

with respect to our psychological relationship to and understanding of spaces.

He offers the image of the shell as a visual metaphor for slow and continuous

formation—a place where life can live, and evolve, but not forever—like a

hermit crab. Rosalia, like Aphrodite, is one such mysterious creature. Rosalia

remained alive inside her stone shell. One account of the finding of Santa

Rosalia’s body reports that as they broke through a stone, they finally located

the saint’s body, petrified, mysteriously enclosed in a rock without openings,

intact like a closed shell. Rosalia comes out of her shell, but only partially.

She is, borrowing Bachelard’s words, half-stone, half-woman, half-dead,

half-alive, preparing always to appear.[32]

In a dynamic escape, Rosalia came alive in 1624, curing all plague, an agent of

resurrection, like her beloved Christ.

[1] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Letter to Clara Rilke,” in Lettres (1900–11), Librairie Stock, Paris, 1934, p. 167.

[2] For the link to EWTN’s Facebook page with the van Dyck image of St. Rosalia, navigate to: https://www.facebook.com/ewtnonline/videos/prayer-to-st-rosalie-for-coronavirus-victims/577992976135374/. Van Dyck’s many paintings of “La Santuzza” established the definitive modern pictorial iconography for this plague saint, including the brown habit of a monastic with her impending crown of roses, as she is ecstatic in her celestially lit ascension, begging indulgence for her fellow Palermitans. Before van Dyck, she was often accompanied by a skull, a lily, a book, and sometimes a pickaxe, used by a local devoté to hack into the cave crevasse where her bones had lain buried.

[3] St. Rosalia was born in either the first century ad or in 1130, during the Norman era in Sicily. This article forms part of the debate proposing a first-century birthdate in the Holy Land as a continuous thread linking her many iconographical iterations and best construing her saintly persona. St. Rosalia was officially recognized by the Catholic Church in February of 1625, when her relics were verified. In 1630, Pope Urban VIII inserted her into the Roman Martyrology, awarding her the double feast days of July 15 (the discovery of her relics) and 5 September (the day of her death). Her first biography, Vitae Sanctae Rosaliae, Virginis Panormitanae e tabulis, situ ac vetustate obsitis e saxis ex antris e rudieribus caeca olim oblivione consepultis et nuper in lucem, was written in 1627 by the Jesuit priest Giordano Cascini, who may have met van Dyck c. 1624–1625.

[4] St. Rosalia’s association with water, limestone caves, and evolutionary passage has been, interestingly enough, picked up by two Palermitan scholars in Luigi Naselli-Flores and Giampaolo Rossetti (eds.), Fifty Years after the “Homage to Santa Rosalia”: Old and New Paradigms on Biodiversity in Aquatic Ecosystems, Springer, Heidelberg/Dordrecht/London/NY, 2010, which celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of publication of one of the landmarks of modern ecological thought, George Evelyn Hutchinson’s “Homage to Santa Rosalia or Why Are There So Many Kinds of Animals,” The American Naturalist, 93, no. 870 (1959), 145–159. Hutchinson’s article has driven most of the research on ecology and biodiversity in the last fifty years. He featured the hermit Rosalia in his title based on her final years spent in a cave adjacent a pond and named Santa Rosalia the patron saint of evolutionary studies in his above-listed paper of 1959.

[5] The “conca d’oro” or “Golden Horn” is so named because of the lush and copious citrus groves that once flourished there surrounded by mountains—now a concrete wasteland since the years after World War II. According to Fabia Ferreri, the area was so named and documented for the first time as the aurea concha in a text by Angelo Callimaco in the fifteenth century (Fabia Ferreri, “Palermo and Its Green Spaces: Between the Past and Future,” in Gaetano Bongiovanni, The “Conca d’Oro”: Images, History, Memories, Biblioteca Alberto Bombace, Palermo, 2015, pp. 58–61.

[6] The 4th is her feast day, and it is celebrated at the hilltop sanctuary and in all churches in Palermo. Rosalia’s Cave Sanctuary was built following the 1624 plague outbreak.

[7] Fig. 3 shows an Open-air atrium of St. Rosalia’s Sanctuary, behind the exterior stone portal. The curtain frames the cave church, which plunges more than eighty feet deep into the mountain. At right, the well of miraculous water, surrounded by ex-votos, still nourishes pilgrims.

[8] The Catholic Encyclopedia reports that her vita (in Acta Sanctorum Septembris, 11 Sept., 278) reflects, according to the Jesuit Bollandist hagiographer J. Stilting (1703–1762), a compilation of local traditions, paintings, and inscriptions. The Bollandist Society was an association of scholars, philologists, and historians who investigated saints’ lives since the early seventeenth century. Their Acta Sanctorum is one of the key sources of hagiographical research. It also states that Rosalia was little known before about 1590, when, in an account by Valerius Rossi, her twelfth-century birthdate and royal descent from Charlemagne is noted, maybe for the first time in early modern history. There is note, however, of churches in Sicily being dedicated in her honor in the second quarter of the thirteenth century.

[9] Pentecost, which takes its name from the Greek word meaning fiftieth, refers to the festival celebrated on the fiftieth day after Passover. Within the Christian tradition, Pentecost commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles and other followers of Jesus, during the period when they were still in Jerusalem, and it is celebrated on the fiftieth day or seventh Sunday after the feast of the Resurrection. It is considered the birthday of the Christian Church.

[10] Found at the end of a review of “The Hussar,” written by George Glieg in The Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, &c, for the Year 1837, James Moyes, London, 1837, pp. 282–283, here p. 283. This “Jerusalem” version was probably more commonly known and accepted in the nineteenth century. George Robert Gleig was a priest, a Scottish soldier, and a military writer.

[11] Fig. 4 shows Santa Rosalia at the summit of her triumphal barge, nestled in “clouds,” among a panoply of carved statues, angels, and luxurious decoration. This triumphal boat reflects the tradition of festa in Rosalia’s honor, since at least the seventeenth century. Fig. 5 the enormous boat/float being tugged through the streets of Palermo toward the marina. The Confraternities of Palermo assemble a new and distinctive triumphal barge over the course of each year.

[12] Glieg, op. cit., ibidem.

[13] The Angevins ruled Sicily after a conflict between the Hohenstaufens and the papacy led to Sicily’s conquest by Charles I, Duke of Anjou. The Aragonese entered after the Sicilian War of the Vespers (1282), when many of the French occupying the island were slain. Shortly after the Peace of Caltabellota in 1302, however, Sicily was divided into two kingdoms and was ruled by the Angevins and the Aragonese. From 1479 on, with the union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, Sicily was ruled directly by the kings of Spain through governors, viceroys, and small numbers of local barons. In the eighteenth century, Sicily passes from royal hand to royal hand: the Savoy, the Hapsburgs, and the Spanish Bourbons, with union with the Bourbon-ruled Kingdom of Naples in 1734. A royal Rosalia, princess and virgin, was better suited to this type of political structure. This Norman heritage of Rosalia is that echoed in the Acta Sanctorum mentioned earlier.

[14] Sicily was a political base for the Byzantine emperors from the sixth century onward. Byzantium conquered much of mainland Italy from its power base in Sicily. The Greek Catholic spirituality of St. Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea (330–379), author of the Rule, also informs Greek Orthodox monastic spirituality. Quisquina is a forested area near Santo Stefano, in Sicily’s rural inland in the province of Agrigento, which housed a hermitage of Santa Rosalia in the twelfth century.

[15] The first Christian shrine on this summit was probably a small seventh-century Byzantine church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Pre-Christian religious uses include an ancient temple to the Anatolian (and later Greek) Earth goddess Cybele and the Phoenician fertility goddess Tanit. Erectensis was the name of the mountain before Rosalia’s cell became a place of pilgrimage. Fig. 6 shows St. Rosalia’s Cave Chapel as it appeared in 1866–1870. Fig. 7 shows that the church today remains essentially unaltered since 1866, although it contains more furniture and decoration.

[16] Competing narratives tell of a Rosalia horrified at the prospect of marriage after seeing a vision of a crucified Jesus, covered in the blood of his crown of thorns, then cutting her hair, forsaking her family, and withdrawing to a convent. Others, particularly the seventeenth-century historian P.A.Tornamira, maintained that she first dwelled in a Benedictine cloister, a position supported by her association with the great Sicilian Benedictine, Saint William of Vercelli, according to Brendan Young, an amateur historian of Catholic saints in a web article entitled “Santa Rosalia: The Sicilian Miracle Worker” (written for the Catholic Family News in September, of 2015). St. William advised Rosalia to remain with the Benedictine hermits at Bivona and Santo Stefano Quisquina, near Agrigento, where she is said to have inscribed, on the walls of her first cave, “I Rosalia, daughter of Sinibaldo, Lord of Quisquina and of the Mountain of the Roses, decided to dwell in this cave for love of my Lord Jesus Christ,” which is captured in some Baroque images of Rosalia. Later, Rosalia left that location and retired to Monte Pellegrino, perhaps with the permission of Palermo’s archbishop, according to Young.

[17] The Jesuits were instrumental and active in promoting Saint Rosalia’s cult in Sicily and beyond. In 1666, she became patroness of all of Sicily, displacing four other early Christian local favorites. Devotion to Santa Rosalia was transported, with emigrant Sicilians in their diaspora, to all parts of the world—especially to Mexico in the nineteenth century and New Mexico in the early twentieth. She is the object of intense devotion and image-making in the iconic Mexican and New Mexican retablo tradition. Towns in Mexico have been named after her, such as one on the northern Baja peninsula on the Gulf of California in the Mulegé municipality. This probably has to do with its association with the sea and sailors. It was also a center of mining early on, and Rosalia’s association with the stone of her mountain retreat could also be another piece of the connective ideological tissue of this eponymy.

[18] The accounts of this narrative vary. Some name the woman Geronima Lo Gatto and not Girolama La Gattuta. Some say Girolama was cured three days after becoming ill, without mounting Monte Pellegrino and fell ill again on 7 May 1624. She then clambered up the hill and was miraculously cured by drinking water of the saint’s cave. She was then instructed by Rosalia to dig for her bones in the same cave, which were turned up on 15 July 1624.

[19] See Fig. 8 for a sculpture of Santa Rosalia reclining on her stone pillow, with angel, skull, walking stick, and crown of roses, in a glass coffin. At left, upon entrance to the cave at Monte Pellegrino, St. Rosalia’s sleeping simulacrum marks the spot where her relics were found.

[20] Hans Belting, in The Image and Its Public in the Middle Ages, Caratzas, New Rochelle, NY, 1981, chap. 5, developed this idea of the iconic “imago pietatis” of the dead Christ as a devotional image. I believe Belting’s idea may be stretched here. Tedesco’s work most likely stylistically reflects the influence of G. Bernini in his majestic and theatrical rendition of St. Teresa d’Avila in Rome’s Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria of 1645–1652.

[21] Images of St. Rosalia from before the thirteenth century are rare, if extant. Many of the images discussed in this paper came to light thanks to an exhibition dealing with the iconography of Santa Rosalia, which took place at the Palazzo Alliata Villafranca, Palermo in 2015 (http://cattedrale.palermo.it/santarosalia/iconografia-di-santa-rosalia/).

[22] St. Elias (20 July), a fifth-century Arab, was educated at an Egyptian monastery and driven out during the Monophysite heresy due to his orthodox position. He journeyed to Palestine, founded a monastery at Jericho, was elected patriarch of Jerusalem, and was exiled again for his beliefs in 513. St. Venera was a second-century Sicilian martyr. St. Oliva was a fifth-century Palermitan virgin-martyr who became a patron saint of Palermo. Their grouping together in Fig. 9 probably speaks to their origins in Sicily (3 of 4) and their association with the monastic life of the Middle East and virginal martyrdom.

[23] Rather coquettish in Fig. 10,with her patrician gold-filigreed gown and robe, coiffed hair, rich jewelry, and martyr’s palm, Santa Rosalia smiles under her crown of roses.

[24] Her followers, the “hermits of Santa Rosalia,” lived in solitude up to the early sixteenth century, dwelling in caves close to where the young hermit saint had lived and died. Toward the mid-sixteenth century, Viceroy John Medina built a convent—still there today—next to the church that included the cave, for the “Reformed Franciscan Order of Santa Rosalia and Monte Pellegrino.”

[25] In Fig. 11, Rosalia has been resurrected as a Franciscan monastic in her roughly textured, girded brown robe. On her robe are strung seashells, associating her with her an ocean voyage. The blackened inside of Rosalia’s right hand and the outside of her left hand show that she has succumbed to the same plague as her fellow Palermitans. She suffers along with them, begging for their salvation, as if alive again in 1624.

[26] Some explanations of the rhyme say the rosy rash was a symptom of the pustules of the plague, and posies, herbs carried as protection, warded off the stinking decomposing flesh. The coughing sound “A-tishoo” (rendered also “a tissue”) signaled the onset of the disease, followed by stomach pain, bleeding, shortness of breath, swelling, fever, fatigue, and decomposition of the skin followed by a painful death.

[27] On the eve of the completion of this paper in late August 2020, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City has finally opened its doors, on a limited basis, to its eager and long-waiting public! And, the Exhibition, “Making the Met” is open to view.

[28] K.Jones, Women Saints: Lives of Faith and Courage, Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY, 1999, viii–ix. Jones discusses the historical differences in the discussion of female saints by family status—virgins, matrons, and widows—and male saints by achievement. The “Universal Roman Calendar” is the liturgical calendar listing the celebrations of saints’ days in the Roman rite.

[29] The procession departs from the Piazza Catedrale, and the carro trionfale is hauled along the Corso Vittorio Emanuele (formerly via Cassaro), passing by Quattro Canti to reach the old entrance gate near the harbor, Porta Felice.

[30] Baumo means Holy Cave in the Provençal language. The Magdalene’s cave becomes a site of pilgrimage early on, having been visited in 1254 by King Louis IX.

[31] I have only examined some of the medieval and later documents regarding the life of Ste.-Dévote at the Palace archives and plan to do more on my next visit. On her feast day, a solemn Mass is celebrated by the archbishop in the cathedral, attended by the prince’s family and many officials. After the ceremony, in the evening, there is the procession with the relics. The tenor of the feast is very similar to that of Santa Rosalia, although on a much smaller scale.

[32] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, Boston, 1994, pp. 106–110.

No Comments