n. 4 / gennaio 2014

Serial power. La politica impolitica delle serie tv

n.3 / luglio 2013

Annisettanta

n. 2 / gennaio 2013

Il viaggio e l'immagine dell'Altro

n. 1 / luglio 2012

Le speranze deluse del POST

n. 0 / gennaio 2012

Che cos’è l’iconocrazia

n. 3 / luglio 2013

Zeitgeist? What Zeitgeist?

Mike Tyldesley

Senior Lecturer in Politics at Manchester

Metropolitan University, United Kingdom.

The Years of Coal; Britain’s long 1970s.

1. Background.

I’d like to start with a suggestion. Following historians like Fernand Braudel and Eric Hobsbawm, who’ve used the idea in relation to centuries, could we suggest that the 1970s were, at least in Britain, a ‘long’ decade? To be more specific, in political terms we can suggest that they started in 1969, with the defeat of the Labour government by the trade unions (i). This was over the legislation called “In Place of Strife”, an attempt to rein in union power, manifest in Britain in the late 60s and then 70s in a wave of strikes, some with union support (“official”) and some not called by unions (“unofficial” or “wildcat” strikes) (ii) . The unions defended the settlement that they then had, which was often called “Free Collective Bargaining”. The political grouping around Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister, suffered a defeat over this at the hands of the Unions and their friends in Wilson’s own Labour Party. The mantle of ‘doing something about the Unions’ passed to the Conservatives, and they had a try in their brief period of power between 1970 and 1974, with the doomed Industrial Relations Act. So if the 70s started in Britain with “In Place of Strife”, they arguably ended in 1985, with the overwhelming defeat of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) by the Thatcher government, a defeat that really marked the end of the unions as a serious factor in British political life, the destruction of the ‘old’ settlement the unions had and the institution of one far more than disadvantageous to them than presaged in “In Place of Strife”.

Harold Wilson

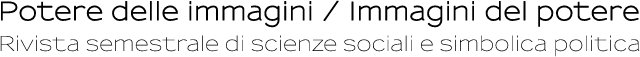

Union power in Britain in the 70s was symbolised by the NUM’s national strikes of the early 1970s, which culminated with their humiliation of the Tory Heath government in 1974. In the face of power cuts and industry reduced to working only three days a week, Tory Prime Minister Edward Heath called a general election in February 1974, in effect asking “Who rules the country”? The answer he received was; “Not you”, and Wilson’s Labour came back to power for a five year spell. The framework of British politics for the years until 1985 was set, and it was Margaret Thatcher who decisively smashed that frame with her defeat of the NUM and then set out on the neo-liberal remaking of Britain. But don’t get the wrong idea; this is not simply a story of politics and strikes. There is a cultural side to it as well. In Italy these were the years of lead. And there was lead here too, though mainly in the North of Ireland as we’ll see. But it seems reasonable to suggest that these were our Years of Coal.

Margaret Thatcher

2. The end of the Football we knew; a sort of digression to start with.

If you go on the internet, or sometimes even at an actual football match, you may come across the slogan “Against Modern Football”. This slogan suggests that the football when every match kicked off at 3.00pm on a Saturday, when most people stood on terraces rather than sat in stands, and so forth was better (in some ways) than what we have today. I have some sympathy with aspects of this view, although I feel that there is a huge amount of often misplaced nostalgia involved, and there is also a great deal of self-deception as to the nature of football ‘as it was’. A different type of football is needed, but a return to the ‘old days’ isn’t necessarily the whole answer. (Were football clubs owned by local capitalists that much better from a fan perspective than football clubs owned by foreign capitalists?)

Regardless; what we can say is that in England football ‘as we knew it’ died on a specific day and in a specific place. And I was there. It was Sunday 6th January 1974. The FA Cup third round, at Burnden Park, Bolton (the ground does not exist anymore) and the match was Bolton Wanderers, of what was then the Second Division, against Stoke City, then a very good First Division club. There were 39,000 in attendance that day under a slate gray sky in the first half and under the beams of the towering floodlights in the second. I was stood with my late father on the Railway Embankment, a huge open terrace that often faced directly into the West Pennine rain. Bolton won 3-2, with the cult hero John Byrom scoring all three of Bolton’s goals (the “hat trick” as we call it in Britain). Byrom had been recently watched by Stoke scouts, who had decided he was “too fat” to be signed by them. So, this was a legendary day for us Trotters, one of many in the 70s which were a turbulent but sometimes quite successful era for the club. But note the day; Sunday. This was the first time professional football matches had actually been played on a Sunday in Great Britain

The Railway Embankment, Burnden Park, 1950s

Technically it was then illegal for clubs to charge for entry to a football match on a Sunday. All 39,000 spectators that day were in theory buying a match programme –actually a one page team sheet- that cost the normal price of admission and entitled you to entry to the stadium. And so the movement towards the “Sky-ification” (iii) of British football started. The dams had been breached. And in a roundabout way this is why ‘ultras’ all around Europe have banners protesting “Against Modern Football”.

This is an example of the way in which the culture of Great Britain (and anyone who suggests that football is not a massively important element in British culture is either ignorant of that culture or a philistine of some sort) and the politics of the years of coal entwined and connected in the way that Britain moved on from modernity into the postmodern society we have today, where no-one would even credit the idea that going to a football match and paying to get in would – or should - be illegal because the match is on a Sunday. (A few Christian hardliners, perhaps some leftists with Union roots, and one or two eccentric football fans excepted.) Why does this event show the intertwining of politics and culture? The obvious question that enables us to see the connection is; why was this the day when football started playing games on Sundays? Was it the result of some liberalisation of social attitudes or pressure from some quarter (television, perhaps) or other? The answer is more interesting. The match was played on a Sunday because Britain was in the period of the three day week caused by the miners’ industrial action (at that point a “work to rule” that resulted in fuel shortages). The way that the three day week affected football was that some matches didn’t kick off at 3pm on Saturdays and some were played on Sundays. Politics and culture intertwined in interesting ways in the years of coal.

3 The Politics of the 1970s.

So, let’s try to characterise the politics of 1970s Britain. Again, the concept of the ‘long’ 1970s is helpful here. With the benefit of hindsight it is clear that what happened between around 1969 and around 1985 is that British capitalism made a very painful transition away from the Social Democratic, corporatist model that had dominated it, powered by Keynesian economic ideas, from the end of the Second World War, and by 1985 it was moving into a new, neo-liberal phase in which the ideas of what was called in Britain the New Right (iv) were intellectually powering political discourse. This political and economic process was accompanied by a similar massive social and cultural shift. In this piece we can only start to see the main elements of these processes. Interestingly, there is at present in Britain a certain degree of interest in the “Seventies”, much of which focuses on the relative ‘strangeness’ of Seventies Britain to contemporary Britain. We seem collectively shocked by just how much our world has changed in what seems so short a space of time. (Perhaps this would bear comparison with the phenomena of “Ostalgie” in the area of the former DDR in Germany?)

The key political question throughout the long seventies was the economy. By the late 60s Britain was clearly lagging behind its competitors. The main economic issue shifted over time; in the mid 60s it was the state of the currency on international markets, then by the late 60s the ‘balance of trade’ (imports as against exports, a figure which is rarely mentioned today). Moving into the 70s proper, the rate of inflation moved strongly up the agenda and really stayed there for the whole of the long decade. In 1973 the ‘Oil Shock’ attendant upon the Yom Kippur war was, for Britain, as for much of the Western World, a huge factor, and of course the fact that this came just at the time that the Mineworkers were increasingly militant resulted in major problems in the British economy. The word used around the middle of the seventies was “stagflation” – prices rising, but production flatlining. A symbolic nadir was reached with the application for a loan from the International Monetary Fund by the Callaghan Labour government in Autumn 1976 (Harold Wilson had retired from the leadership and was succeeded by one of the men who had beaten him over “In Place of Strife” back in 1969; but this was not a shift to the left for Labour in any way.) At least for the right wing press, this was Labour’s confession of Britain’s slide into economic, political and moral bankruptcy, a view touted extensively in the USA at the time. Interestingly, Andy Beckett, in his history of the 70s, points out that it was actually the twelfth time a British government had taken a loan from the IMF in the post-war era. That said, imagery counts for an awful lot in politics, and there was something rather symbolic about that loan. Already by the late 1970s even Labour politicians were listening to the voices of the New Right about the need for public spending cuts – and enacting some cuts. The Conservatives, especially after Margaret Thatcher became their leader in 1975, were very open to the message that was coming from the New Right.

In the late 1970s the New Right were also known as Monetarists. This was because at the time the key question was how to defeat inflation. Keynesian influenced economists argued the “wage-push” theory. This suggested that inflation was caused (crudely) by over-powerful trades unions achieving large wage increases and companies pushing up prices to ensure that they actually made profits. Unions were in a strong position because, firstly, they were popular; union membership peaked in 1980 at just over 12 million. (That was in a population of around 55 million. Union membership is now rather less than 6 million in a population of around 65 million.) Secondly, they were reaping the benefit of the fact that since the end of the Second World War unemployment levels had been low, giving labour, as a factor of production, a degree of power.

Monetarists, by contrast argued the view that inflation was caused by governments printing money. On this view it wasn’t the trade unions that caused inflation, but (in effect) the Central Banks. It was around this idea that the New Right gained a bridgehead into British political life. On the wage push view, the key policy, and one pursued throughout the seventies by both Labour and the pre-Thatcher Tories, was to try to get some sort of national policy limiting wage rises, whether compulsorily or – and this was Labour’s approach with what it called the Social Contract - by getting some sort of agreement with the Unions. (Labour politicians favouring this approach tended to quote Germany and Sweden as examples of what could be achieved by it.) Monetarists dismissed this approach and said the answer was straightforward; cut public spending. There was another view; on the left of Labour and in the small - but influential in the trades unions - Communist Party an Alternative Economic Strategy emerged around the idea of import controls, free collective bargaining for the Unions, and an increased use of nationalisation – for instance of the finance sector.

The paradox is this; the Keynesians, although putting the blame for inflation on trades unions wanted to get them involved in the solution to the problem. The New Right, although advancing a solution to inflation that in many ways suggested that trades unions were not the key issue, due to their fierce advocacy of free markets – untrammelled by ‘distortions like unions- saw the trades unions as, to use a term that became rather notorious at the time of the miners’ strike of the 1984/5, “the enemy within”. By the early 1980s, with inflation no longer the key issue, the ‘problem’ had again moved on, and now it was about making Britain an “enterprise” economy with high rates of growth and the like. The ascendant New Right felt that the unions and the “rigidities” they imposed in the workplace prevented this. “Flexibility” became the key – and in no small measure remains so.

So, by the mid-1980s, as Britain left the ‘long 1970s’, the Thatcher government was ready to do as much damage as they could to the trades unions, deregulate industry as much as they could, and get as much of the economy out of the public sector as they could. With the defeat of the Miners in 1985 the way was pretty much clear for them. The situation in Britain in 1969 was of an extensive public sector, in which utilities and whole aspects of infrastructure in the country were in public hands. (Probably only Austria of non-Communist countries in Europe had a more extensive public sector than Britain.) By the end of the ‘long 1970s’ this was still the case; but in the following few years (roughly 85-92) Thatcher’s and her Conservative successor Major’s Privatisation programmes and some allied measures in local government changed the situation massively.

The sorts of issues we have discussed here were the prism that many of the other political issues of the day were seen through. The seventies saw the accession of the UK to what used to be known in Britain as the “Common Market”, or EEC – now the European Union. Arguments around this were conducted (even at the time of the referendum on membership, which was held in 1975, after a renegotiation of terms by the Labour government, two years after the Tories took Britain into the Union in 1973) in very economic terms, a practice that continued. Much Tory Euroscepticism started with the Thatcherite argument that Britain was ‘paying too much’ (money) for its membership. Political issues around European integration and Federalism on came onto the agenda very much later.

Throughout the long 1970s there was one other major issue that cast a brooding shadow over the politics of Britain, and this was where Britain faced its own “years of lead”, namely the North of Ireland. Before discussing what are still known to all as “The Troubles” it is worth pointing out that there was a very small mainland equivalent to the Red Brigades and the Baader-Meinhof Gang. This was the “Angry Brigade”. Active in 1970 and 1971, they undertook 25 bombings, causing a certain amount of damage to property and slightly injured one person. Other than a rather long trial of some of the alleged members of the Brigade, it had little impact.

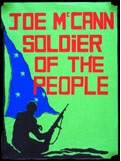

On the other hand paramilitary groups on both sides of the conflict in the North of Ireland had significant memberships, support, and undertook a level of armed activity that was probably the most significant in the whole of Europe given the size of the area that they were operating in, with the possible exception of the Basque country. In the early 1970s whole areas were virtually under the control of the two Irish Republican Armies that operated on the Catholic/Nationalist side (the “Officials”, the original IRA, whose move towards class politics and Marxism triggered the growth of the splinter, more traditionally Nationalist, “Provisionals”. The “Provisionals” went on to become the more powerful of the two groups. The “Officials” went on ceasefire in 1974, the Provisionals only following in the late 1990s. The “Provisionals” now operate politically as Sinn Fein and have a significant presence in the North and South of ireland, the “Officials” operate north and south as the small Workers’ Party) and on the Protestant/Loyalist side the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Outside Britain and Ireland the activity of the IRA is fairly well known, but the loyalist bodies (which at times appear to have collaborated with sections of the British state, although there have also been recent revelations of the extent to which the Provisional IRA was infiltrated by the British secret services, in a rather different process) are perhaps not as well known. Any reader under the impression that loyalism was simply a sort of shadow puppet conjured up by the British to justify their continued rule in Northern Ireland should read Dominic Sandbrook’s account of the Ulster Workers’ Strike of 1974, when working class loyalists with roots in the loyalist paramilitary groupings (and the active support of these bodies) brought down the power-sharing executive, a British government supported initiative to get the nationalist minority into the devolved government of the province. (Not a million miles, perhaps, from the results of the much later Good Friday Agreement, which now sees a devolved Ulster ruled by a coalition of the Democratic Unionists and Sinn Fein, an outcome which would have left anyone in the 1970s open mouthed in incredulity.) It is possible that the UWC strike was the single most powerful political display of working class power that Western Europe has ever witnessed, although the proviso would have to be made that upwards of a third of the working class in the province was quite deliberately excluded from it. (v)

Official IRA Poster from 1972, commemorating Joe McCann, Commander 3rd Belfast Battalion OIRA, shot dead by British Paratroopers.

Ulster Workers’ Council Strike, 1974 (Possibly UDA members marching.)

British troops had been deployed into Northern Ireland in 1969, as the security situation there worsened, especially in the aftermath of attacks on Civil Rights marches by the Royal Ulster Constabulary, a body that was perceived – certainly by the Catholic minority - as basically being a Protestant force. The situation throughout the long Seventies was a long disaster for the British political elite, with one failed initiative after another. The effect on the mainland was debilitating, too. The Provisional IRA intermittently bombed targets in Britain (a practice that continued basically until they decided that they were concluding the armed conflict). Some of these bombings seemed quite spectacularly counter-productive, most notably the Birmingham Pub Bombings where 21 were killed when the Provisionals bombed two pubs in the city centre. The rather strange lack of litter bins on British railway stations is an after effect of this bombing campaign. Basically, after years of attempting to “do something” about the North of Ireland, by the later phase of the seventies Britain just settled down to wage a long security campaign there. This was symbolised by the last 1970s Labour Secretary of State for Ireland, the dour Roy Mason. This approach was largely continued by the Thatcher government in its initial years, and saw the H-Block situation, and even the bombing of the Tory Party conference at Brighton in October 1984.

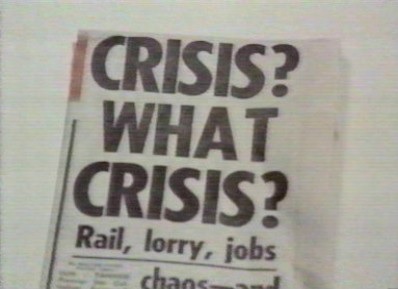

The seventies “proper” ended with the defeat of the Labour government lead by James Callaghan at the hands of the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher. Labour had come in during the chaos of the Miner’s dispute and the three day week. The Labour approach to trying to rein in inflation – a sort of attempted voluntary but sometimes imposed deal with the trades unions called the Social Contract – pretty much collapsed in the winter of 1978/79. This became known as the Winter of Discontent. The problem was that private sector workers were forcing through wage increases that weren’t being matched by what the government was allowing to workers in the public sector. The result was a strike wave and some fairly serious social dislocation. James Callaghan went to an international summit in Guadeloupe in January 1979. On his return he gave a press conference at Heathrow airport against the advice of some of his team. Harried by the press he appeared to wish to deny that Britain was in some sort of chaos. Although he never actually said the words, the right wing tabloid The Sun had as its headline the morning after “Crisis? What Crisis?” Image was more important than anything else, and the phrase stuck. Callaghan appeared out of touch, and Thatcher, more than happy to suggest Britain was in crisis was on her way to Number 10 Downing Street. The way was set for the almost inevitable conflict with the miners, a conflict that was timed well by the government, was run in such a way that the Miners had little or no choice but to react to provocation, but which was handled in a way by the Miner’s leader, Arthur Scargill, that made victory for the government almost inevitable (vi). The seventies wound down with the defeat of the most powerful of trades unions. The road to a neoliberal Britain was wide open.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dX06xqN6710

Link to Youtube film of Callaghan’s “Crisis, What Crisis?” Press Conference

The front page of The Sun newspaper the following day.

4. British Culture

Just as the above has been a very schematic outline of the political seventies in Britain, what follows will inevitably also be a rather rapid round up of socio-cultural developments. The seventies were a period of massive change in British culture – although in that respect, it has to be said that the same can also be said of the sixties and eighties, and probably every decade since. In recent decades arguably cultural change has been intimately connected with technical changes. So, the growth of personal computing, the internet, mobile, then ‘smart’, phones; all these (and more) have been at the heart of recent cultural changes that make British society massively different in important ways to what it was like as recently as –say- 1995. The type of cultural turbulence in the seventies was rather different. A lot of the key technologies were in place by 1970, and changes were relatively minimal. In the musical field the seventies saw the speeding up of the shift from the “single” to the “album” as the key sales unit in the music business, but in truth this was something that had been happening in the 1960s, and even in the early 1980s the 7in single remained an iconic consumer good.

The Compact Disc was yet to come (I remember the first time I ever saw them; in a very upscale hi-fi shop in Oxford in 1983. I was amazed that “Too Rye Aye” by Dexys Midnight Runners was available in the format. Surely everyone who wanted it had it on cassette?) Home video was just about coming in; a tutor at Nottingham University used a VCR machine to show us his Open University programmes in our seminars in 1978. We felt slightly unsure about this; shouldn’t he be “actually teaching us”? By around say 1984/5 both these technologies were really making an impact, and the cost of buying (or, with VCR, often renting) a system for home use were coming down to such an extent that they became widely, almost universally, used.

Music was still primarily heard via the system of radio, and in the seventies (even defined in terms of the “long seventies”) the network of state and some local private stations stayed pretty much the same. (In very broad terms it still has, but radio as a medium is no longer as popular or as central as it was.) TV was probably the dominant medium in seventies Britain, and the system of two BBC stations and one Independent station stayed broadly similar throughout the decade. (The state owned BBC television started broadcasting in 1932, ITV – the commercially owned channel - in 1955, BBC 2 in 1964, and Channel 4 in 1982). The advent of Channel 4 in 1982 was, in retrospect, the start of a process that has seen a massive proliferation in the number of TV channels, both “free”, “terrestrial”, and “pay” and “satellite”. But one can see that the seventies saw little real development in the configuration of the system until towards the end of what we have defined as the ‘long’ version of the seventies.

This was very much the era of ‘mass’ television, where certain programmes had enormous audiences. An often quoted example is The Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show of 1977, with an audience measured at 28 million by one method and 21 million by another. Audiences today are fragmented between far more providers, and as a result the old phenomena of ‘everyone’ at work or at school or at university being able to discuss last night’s edition of whatever (at school for me it was Monty Python’s Flying Circus that stays in the mind in this respect) has gone. A programme that is my favourite may not even be being watched by the bulk of my friendship circle. The person that shares my office at the university might be able to watch channels I cannot even see (because I don’t pay extra for them) and so we can’t discuss what we have been watching. Against that, mechanisms like twitter mean that I can be instantly in touch with people far distant from me watching what I am watching, and if I know other people watching a show that interests me I can use SMS or Blackberry messenger to be connected and instantly comment on a show. (vii)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iO9noBmj5rk

Link to Youtube film of Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show 1977 Sketch with Elton John.

Let’s try to pick up on some important cultural trends in the Britain of the 1970s. Popular Music in Britain had achieved a position of world significance in the 1960s, with the rise of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the whole “British Invasion”(of the USA) phenomenon. This position continued into the seventies, but the styles of music changed. Things never stay the same very long in this field, even if on occasions the actual performers do. (One could chart the careers of a number of performers who started with one genre, and moved through a whole series between the 60s and the 80s. Andy Summers, for instance started in the mid-60’s with legendary R&B/Soul band Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band. This morphed into acid rock band Dantalian’s Chariot. When this broke up Summers played with The Soft Machine, The Animals and various other outfits before spending the end of the 70s and the first part of the 80s in pop/rock/reggae band The Police. His career continued, and is only mentioned here to show that waves of adaptation in the music scene don’t necessarily mean wholesale changes of personnel.)

In the early 70s the two most prominent trends were Progressive Rock and Glam Rock. “Prog” can be seen in a line that goes back from psychedelic rock, through the sort of electric blues played by bands like Cream to the Rhythm and Blues boom of the early 60s, which inspired bands like the Rolling Stones. Someone like Jack Bruce, who played in Cream had earlier played in bands like The Graham Bond Organization which had full blown horn sections and covered Stax hits. By the early 70s bands like Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer(ELP) largely featured guitars, drums and keyboards, with the rise of the synthesizer being notable here. It’s possible to stereotype this music as typically having 20 minute long songs featuring lengthy guitar and/or keyboard solos. Although Prog bands may have issued singles in the 70s, the album or even double album was their natural territory. (viii) (In some respects Prog is the seed bed for the subsequent Heavy Metal music, but it is probably not as simple as that statement makes it sound.)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-HN5XqDjTE

Link to Youtube film of ELP performing Fanfare for the Common Man live in 1978; example of “Prog”

Glam rock was the downmarket equivalent of Prog, with a stronger emphasis on sales, singles and riffs in the music. Bands such as Sweet and perhaps Slade were good examples of this trend, with David Bowie and later Roxy Music occupying a sort of territory in between; getting good single sales, but also retaining a certain amount of critical credibility. With Glam (the word comes from Glamour) there was an extremely strong emphasis on the look of the band, with ‘outrageous’ clothing being de rigueur. These two forms did not exhaust the musical scene, and to some extent, as with any such summary, a great deal of liberty has been taken here. Up and down the country there were determined and devoted audiences for musical forms such as Soul (Northern and Modern), Funk and Reggae, with reggae being especially popular among Black youth. The seventies were, after all, the main years for Wigan Casino, the mecca of Northern Soul. But that remained very much a rather hidden subculture. You’d have been very lucky to hear a Northern Soul song on Radio One, the BBC’s “pop” channel.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQj9Gbr2hx8

Link to Youtube film of Sweet performing Blockbuster on Top of the Pops in 1973. Example of “Glam”

The point of the summary is really to set the scene for the explosion of 1975 and 1976. What happened in 1975 and 1976 was Punk, or the New Wave. At the musical level a reaction against material like Glam and Prog, there was a whole overload of cultural and political significance that is sometimes hard to credit when one listens to some of the music that was marketed under the punk banner – a lot of it basically sounds like typical early 70s rock, and has lyrics as banal and sexist as that kind of music did. (The Stranglers are a fairly obvious example of this.) Some punk bands were simply hastily reconfigured bands who had previously played other genres of music (quite a number from what had been the burgeoning “pub rock” scene) and adapted quickly to changing tastes. Punk shot up almost simultaneously around the whole country in 1976. A key instance of this was the Sex Pistols gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on the 4th June 1976. This galvanised the punk scene in Manchester, and presaged a punk boom across the country.

Punk can –whatever the caveats about quality, originality or other issues – be seen as one of those massive explosions of a cultural type that set an agenda in certain ways for years to come, and which serve to show what is happening at the deeper levels of society. Musically, it was finished quite quickly. By the end of the 70s the New Wave was in some ways “over”, and a ska revival sound called Two Tone (based around a record label of the same name) which had strong roots in the industrial Midlands (The Specials from Coventry) as well as London (Madness) was perhaps the key new popular style. Various forms of “post-punk”, including some very deliberately political musics and some rather musically accomplished efforts also gained a hearing. But in a sense the limited lifetime (except for the subcultural continuations of punk that still exist to this day in things like the hardcore punk and straight edge punk scenes) isn’t the point. The explosion was the point.

How did this cultural explosion relate to the politics of the ‘years of coal’? This is actually a rather tricky question. Quite a few punk bands had little or nothing to say about ‘politics’; The Stranglers would be an example, as would Eddie and the Hot Rods (now forgotten, their “Get out of Denver” was the best of the early new wave by some distance). On the other hand several of the instigators of punk – and one thinks here most obviously of Malcolm McLaren the manager/eminence grise of The Sex Pistols, and his co-operators Jamie Reid and Vivienne Westwood - had been influenced by situationist thinking (which in truth never really had a major audience in Britain, although interestingly may have been important for some of those involved with the Angry Brigade). As such the approach they took was extremely sceptical about conventional politics, including those of the left, something very evident in songs like “God Save the Queen” or “I am an Anarchist”. These kinds of songs scarcely fit with the ethos of the British leftist parties, which by the mid to late 1970s were gaining a degree of influence, especially in the universities. In “God save the Queen” from 1977 Johnny Rotten famously sang “There ain’t no future in England’s Dreaming”, and the phrase “No future” appears as a sort of motif throughout the song. To the earnest young leftist rebels of the mid 1970s this would appear as heresy; of course there was a future – The Revolution, usually lead by The Revolutionary Party.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rnmNHGVC1co

Link to Youtube film of Eddie and The Hot Rods, performing Get out of Denver, live 1977

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YwXc-RFL-zk

Link to Youtube film of Sex Pistols performing God Save the Queen live in 1977.

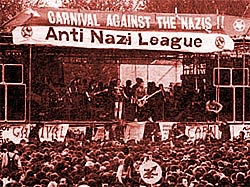

Some sections of the punk explosion got tied into the efforts of one of Britain’s versions of The Revolutionary Party, the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP). In reaction to an ignorantly racist rant by Eric Clapton at a concert, some of the SWP’s cultural operators, along with allies formed a movement that did have something of a mass impact; Rock against Racism (RAR). An aside here; racist, far right politics had been a sort of sub-text to British politics throughout the long 1970s. In April 1968 a front ranking Conservative politician, Enoch Powell had made a speech in Birmingham known as “the Rivers of Blood” speech. (ix) This speech was an attack on government toleration of immigration to Britain from former imperial territories such as India, Pakistan and the West Indies. It acted as a sort of galvanisation for the far right in Britain and by the mid 1970’s a party formed from the failed groupuscules of the British racist right, the National Front, was making headlines. (x) (The speech also lead to Powell’s departure from the Conservative leadership, although he had a clear and abiding appeal to the party’s rank and file.) This was because of a number of factors; it was gaining some degree of support at elections, it was putting on members, and perhaps most importantly it was aggressively conducting itself on the streets, marching in areas with heavy immigrant populations and recruiting from among sections of football hooligans. RAR was as much an attempt to take on the National Front as a reaction to Clapton’s inanities. Interestingly, the National Front would signify its presence by painting NF on walls in an area. This was often reconfigured to read “No Future”.

RAR, and the allied Anti-Nazi League, made an impact at street level, most notably with a series of very large demonstrations which ended in concerts. These were sometimes called “Carnival against the Nazis”, and in the histories of the 70s these are discussed. So, you’ll find accounts of the April 1978 London event which ended at Victoria Park with a concert featuring punk bands The Clash, the Buzzcocks and The Tom Robinson Band. The organisers had expected 20,000 – over 80,000 showed up. That summer there was a huge rally in Manchester that remains the largest demonstration in the city in my memory.

Victoria Park Rock against Racism rally April 1978; The Clash onstage.

So, some elements in punk got ‘politically involved’. In retrospect this involvement is sometimes said to be what “saw off” the National Front. It perhaps prevented the Front from gaining anything other than a marginal presence amongst the youth of the country. In fact rather more significant in ending the threat of the far right in the late 1970s was the interview Margaret Thatcher gave to a TV programme on the 27th January 1978. In this she twice referred to the feeling that “people” (ie white people) might have of being “swamped” by “people with a different culture” (ie brown and black people). The balloon of the National Front was pricked – their erstwhile and would be voters had a home to go to other than the Front. The Conservatives protected their right flank. Thatcher never repeated this rhetoric, but she didn’t have to. As Enoch Powell pointed out, if you want to convey your meaning to the electorate, you only need to do so once. (xi)

So here again we find a complex intertwining of the political and the cultural in the “years of coal”. At the time it was part of the common sense of the era that punk “was” political. But at the time it was quite hard to say exactly what that meant, and even with the benefit of a lot of hindsight, it’s still quite hard to say what it means.

Not that music was the only area of the culture that saw huge upheavals. The theatre reflected the years of coal with the rise of a generation of highly political (left-wing) playwrights. This was the period of Howard Brenton, David Hare and Trevor Griffiths. Griffiths’ 1975 play Comedians (about a group of Manchester would-be stand-up comedians) transferred to Broadway. His earlier play dealing with British Trotskyism, The Party, had been produced at the National Theatre and starred Laurence Oliver as a veteran Trotskyist (the person it was allegedly modelled upon was later humbled by a sex scandal of fairly major proportions). By the mid 1970’s Griffiths was writing major series for television (Bill Brand) that brought his political themes to the most popular of forums.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GUEB4PAZMRk

Link to Youtube film of the TV version of Trevor Griffiths’ Comedians.

But for the theatre this was not just an age when a generation –now very much forgotten – wrote the ideas of the left into their plays. This was also the era of the touring leftist theatre groups. Perhaps the most famous in the 1970s was John McGrath’s 7:84 Theatre group. (7% of the population own 84% of the wealth, as I explained to the vice-chancellor of Nottingham University at a drinks party in 1977 when he enquired what the badge I was wearing signified.) McGrath had been a writer on Z Cars, an extremely important TV police series of the 1960s and early 1970s. He moved into what was called at the time “agit-prop” theatre and his company toured leftist plays around the country. I saw them several times and the actors I saw in their shows included a number whose faces subsequently became nationally and indeed internationally famous.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sb3qbFcLYZc

Link to Youtube film of the BBC TV version of The Cheviot, The Stage and the Black, Black Oil, 7:84 Theatre company’s most famous production originally produced in 1973.

Griffiths and McGrath had both tried their hand at writing for television. In a sense for leftists this was the obvious move. The working class watched television in the 1970s; by and large it didn’t go to the theatre. So if you could get your material on television, you might be able to make an impact - politically. And in the 1970s Griffiths and McGrath were not alone, with other committed leftists - Colin Welland, Ken Loach, Jim Allen and others like Dennis Potter, a leftist of a rather different type to those mentioned and perhaps ultimately the most important in TV drama- getting important opportunities to put over their ideas. It may be the vagaries of memory, but one recalls that the BBC’s Play for Today slot was an important vehicle for this school of writers. This tells you something about the theatre in 1970s Britain; the West End still in the long process of emergence from its pre- and post-war painful respectability, an emergence that started symbolically in 1956 with Look Back in Anger by John Osborne, and which was pushed strongly by the almost legendary (and leftist) figure of Joan Littlewood at the Theatre Workshop at Stratford in London’s East End (not the one in the Midlands where Shakespeare came from).

It also tells you something about how British television was starting to emerge from the grip that the founding figure of the BBC Lord (earlier John) Reith. Reith had run the BBC true to his dour Scottish Presbyterian worldview. It was safe and tame, and could be summed up as speaking in the Queen’s English, and always wearing ‘black tie’. It was conservative “with a small ‘c’”, and perhaps sometimes a large one too. The subsequent Director General, Sir Hugh Carleton Greene (brother of the novelist Graham Greene), had started to loosen things up considerably in the 1960’s. A good example of this was a programme that started in 1969, continuing to 1974; Monty Python’s Flying Circus, a sort of surrealist comedy show produced by a team of former Oxford and Cambridge students. Python would have been unthinkable previously; the earlier BBC effort at satire, That was the week that was (1962/3), was so successful that it had to be ended prior to the 1964 election because it was a source of worry that it might be seen to affect the vote. Python couldn’t affect the vote; what political conclusion could you possibly draw from it?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vuW6tQ0218

Link to Youtube film of The Dead Parrot Sketch, perhaps Monty Pythons Flying Circus’s most famous sketch.

Members of the Python team went on to do other things; bizarrely John Cleese more or less reinvented and reinvigorated the staple of British television comedy, a format called the ‘situation comedy’. Most of these were very tired and tame affairs by 1975 when Fawlty Towers hit the screen (a second series aired in 1979). Having deconstructed TV comedy in Python Cleese just showed everyone else how to do it if you wanted to get laughs from traditional formats. The Pythons’ swansong – in reality- was their film Life of Brian that came out in 1979. It caused a major scandal both in Britain and the USA, with its implied satire of Christianity. The one thing that the Python’s humour never really exploded was the inherent male chauvinism in much British culture. Watching Python today this is what hits you; so much of it is based around the idea that women are inherently funny (and therefore inferior). There is also much humour in it that the politically correct might construe as anti-homosexual; the problem with that approach is that one of the team was an “out” gay man (Graham Chapman), who had some clear purposes in mind in what he was doing with the show.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tcliR8kAbzc

Link to a Youtube film of a clip from of Fawlty Towers.

British culture continued in the 1970s to liberalise in ways that had started in the 1960s, but the point about Python and its chauvinism raises a more general one; feminism and gay liberation had started their challenge to the sexual ideologies that still had Britain in their grip. But the 70s was not the era in which the challenge really started to gain traction. That would come later. A comparison of the reactions to single sex marriage in Britain and France over the last couple of years shows how much has changed (which is not to say that there isn’t much more ground for women, LGBT people and others to make). There has been nothing in Britain remotely resembling the substantial, street level and sometimes violent opposition to single sex marriage seen in France. Some of the language used in the street demonstrations and rightist newspapers in France on open and wide sale would probably instigate arrest in Britain. It’s worth pointing out that this measure has been introduced over here by a centre right government, and that within the ruling coalition the group of Conservatives around David Cameron are probably more identified with it than are the Liberal Democrats.

This has been an effort to sum up a very fluid picture in British culture. The ‘years of coal’ were reflected in music, theatre and television. Doubtless the same could be said for other art forms. And that reflection was never a simple affair – though in the hands of some of the agit-prop playwrights and more politicised punk bands (say Ken Loach and The Clash for examples) a degree of leftist simplicity was fairly evident. British cinema, which for most of the 1970s seemed to survive by turning out an endless stream of “sex comedies” (whether of the ‘double-entendre’ type embodied in the Carry on.... films, or the more soft-pornography types such as the Confessions of a ....... franchise) actually was capable of producing some interesting and serious films that reflected and commented upon the Britain of the day without being simple platforms for stereotyped political viewpoints. One thinks of Lindsay Anderson’s O, Lucky Man! (1973 ) –itself the follow up to the brilliant satire on the English Public Schools, If .... (1968 ) - and also Peter Medak’s The Ruling Class (1972 ) featuring Peter O’Toole.

Conclusion

The ‘long’ 1970s, the “years of coal”, in Britain were very much an era of transition (there’s an obvious sense in which all periods of time are). The post-war Keynesian Social-Democracy that characterised the previous era in British history, was giving way. Hindsight suggests a sort of inevitability in its replacement by Neo-liberalism, but that wasn’t the way it felt at the time. For much of the 1970s large sections of the population – never a majority – felt that it should give way, but to various visions of a further left Britain. Serious discussions about the best way to replace British capitalism and the best form of Socialism with which it needed to be replaced went on in the 1970s in a way that would appear anachronistic today.

This process of transition was not simply political. It was cultural and it was social. Britain was on the move not only from the kind of economy that we had had, but also from the kind of cultural and social norms that had been prevalent. In some ways this continued trends to social and cultural liberalisation that been evident in the 1960s; homosexuality had been decriminalised, equal pay for men and women had been legislated for (if not implemented), the Race Relations Act had offered the non-white population some protections and redress, and theatre censorship (done via the “Lord Chamberlain”, a typical bit of British constitutional neo-medievalism) was ended. None of these developments were overturned and in some ways this kind of legislative programme was continued in the 1970s. But in the 1970s the adequacy of what had been the fairly standard view of the ‘liberal’ middle classes on these issues started to come under a serious and radical challenge. It is worth stressing, though, that this challenge was not straightforwardly leftist, and that elements of it led into the Neo-liberal, or Thatcherite, vision for a new type of society. It is far from clear that the end of football starting at 3pm on a Saturday the way it had represents a leftist or a rightist change. Or even if such changes can be characterised in that way.

The 1970s were, then, an importantly formative era, but a sort of ‘Janus’ era as well. One that presaged a new type of Britain, but also one that was undeniably still the old Britain (indeed, aspects of that old Britain reached their apogee in the 1970s – the 74-79 Labour government took some industries into public ownership and the public sector of the economy probably reached its greatest peace time extent sometime around 1977.) The defeat of the trade union movement in 1985 has proved definitive, though. The movement has been in decline ever since and even a period of 13 years of Labour government has not seen the decline seriously reversed. The Years of Coal are now definitely history.

(i) In Britain the trades unions are largely affiliated to the Labour Party. This was, perhaps, more of an important political factor in the era before Tony Blair and his ’New Labour’ settlement in the party, although this point flares up every so often when party funding is discussed in the media, as it has recently. (British political parties are, in broad terms, not state funded.) In fact the power of the unions in the party diminished from around 1985, a date we’ll come to in the text. All that said, the fact that the party and the unions were in conflict in 1969 was a major issue.

(ii) Andy Beckett, in his interesting book on the 70s in Britain, When the lights went out, Faber, London, 2009, gives a couple of quotes from the late left wing historian Raphael Samuel, which sum up very well the exact situation on industrial strife in Britain at this time, and help to explain some of this terminology. See page 56.

(iii) Sky is the main satellite and pay per view channel in Britain, and they have a significant proportion of televised football under their control. The Bolton Wanderers versus Queens Park Rangers game on 24th August 2013 kicked off at 12.15pm, instead of 3pm, because it had been selected to be broadcast on Sky.

(iv) The New Right in Britain means something very different from its meaning in continental Europe. In France it is a term that might be applied to the likes of Alain de Benoist and the GRECE organization, or similar thinkers in –say- Germany or Italy. In Britain, by contrast, the term started to be used in the mid-1970s to describe the ideas of what would today probably be called neo-liberalism. The key thinkers signaled by the term New Right in Britain would be Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman. Strangely, despite the fact that the “Nouvelle Droite” would be completely opposed to this strand of thought, the way the New Right organized in Britain was in bodies quite similar to GRECE; these were called “think tanks”, and were very far from being political parties. Probably the most important in the 1970s was a body with the anodyne name Institute of Economic Affairs. At a populist level, a term that replaced or substituted for New Right was “Thatcherism”.

(v) Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun. Penguin, pp 109-123.

(vi) Crudely, the argument would be this; one of the problems for the Miners was that at least one major coalfield did not support the strike (Nottinghamshire). This was on the grounds that they had not been balloted; the leadership of the union simply called the strike. Scargill, a Labour member at the time, but an ex-Communist, and a determined Leninist, would not compromise on the demand for a ballot. Getting the Nottinghamshire miners on side with the strike might not have resulted from a successful national ballot, but their position would have been massively weakened had they chosen to work after a ballot had resulted in a strike vote. And had the Notts miners come out, then the whole situation for the strike would have been different. The battle might not have been won, but, of course, we’ll never know.

(vii) Half the fun of The Returned (aka Les Revanants) for me were the instant and highly funny comments from one of my friends that arrived as I was watching the show. In the 70s I could do this with someone there in the room with me, but not someone any distance from me..

(viii) The law of karma arguably teaches us that “what goes around, comes around”, and we are currently seeing something of a mini-revival of Prog music in Britain, with some of the original bands getting back on the road, and magazines catering to fans with titles such as Prog.

(ix) The actual phrase “Rivers of Blood” does not appear in the speech, although something very similar does. Once more, image trumps reality.

(x) Powell was never a member of this party, even after he left the Conservatives. He went from them to become an Ulster Unionist MP. He was, in fact, also an early advocate of “New Right” (ie neo-liberal) free market economics, something that British Fascist parties have tended not to favour.

(xi) Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun, p 595

Annisettanta

di Giuseppe Cascione

Saggi

Prima di Zanardi

rivoluzioni grafiche e narrative nel calore degli anni '70

di Stefano Cristante

Zeitgeist? What Zeitgeist?

di Mike Tyldsley

"Nuovo fascismo" o neoliberalismo? Michel Foucault e l'affaire Croissant

di Alessandro Simoncini

1977. Prove (riuscite) di esorcismo del dissenso politico

di Giuseppe Cascione

Parco Lambro 1976 e la falsa utopia del proletariato giovanile

di Mario De Tullio

Pop anni settanta

di Ivan Scarcelli

Lotta Continua

di Fabrizio Fiume

Immaginario armato

La scelta dei simboli nella strategia delle prime BR

di Gabriele Donato

Berlinguer e il settantasette

di Claudio Bazzocchi

Declinazioni cinematografiche della scelta e della responsabilità

di Luana Piscopo

Prima della "Milano da bere". Memorie della Scighera

di Aldo Vassallo

Icone di piazza: le donne nelle fotografie di Tano D'Amico

di Laura Labate